Is Piss Christ Good Art? Part III – Experiencing Art

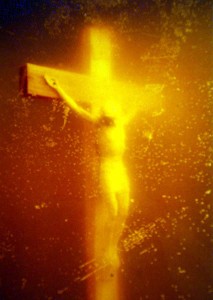

After defining art in the first part of the series and examining the need to think critically about it in the second, it is now possible to investigate the ways in which we might respond, and perhaps should respond, to works like Andres Serrano’s Piss Christ. We can now examine what should happen when we view such a work.

After defining art in the first part of the series and examining the need to think critically about it in the second, it is now possible to investigate the ways in which we might respond, and perhaps should respond, to works like Andres Serrano’s Piss Christ. We can now examine what should happen when we view such a work.

In western culture, particularly the American brand, the first notion that enters a viewer’s mind is to search for meaning. The typical viewer looks at the artwork and automatically asks, “What is it?” By this, they mean, “What does it mean?” This is seen in people’s reactions to abstract art. When first encountering an abstract work, most people will immediately begin asking questions like, “Is that squiggly line supposed to be a person?” Or, “What feeling is this supposed to make me feel?”

Our culture has taught us to look for content first and foremost. We tend to put a dichotomy between form and content, and we then tend to see form as a mere means of portraying content. However, this all falls apart with abstract art. In such art, the form is the content. The squiggly line is just that, a squiggly line.

In placing content in contrast to form, and often in priority over it, we inhibit our ability to fully experience art. For example, if a man was to look at a sunset and then immediately ask “What am I supposed to feel?” or “What is it?”, we would agree that he has failed to fully experience the sunset. Though such questions are not inappropriate on their own accord, they reflect a failure on his part to aesthetically experience what lies before him.

So it is with art. Art should not be experienced primarily with an eye for content, but as an aesthetic experience. It would surely be sad if sunsets were only ever experienced as bunches of photons being refracted by the earth’s atmosphere and not as the aesthetic experiences that they are for most of us. What I mean to say is that something is lost if we only ever look at art as a vehicle for content and not also as form.

Joseph Pieper illuminates this tendency to make everything into a rational experience in his essay Leisure: The Basis of Culture.

Ratio is the power of discursive, logical thought, of searching and of examination, of abstraction, of definition and drawing conclusions. Intellectus, on the other hand, is the name for the understanding in so far as it is the capacity of simplex intuitus, of that simple vision to which truth offers itself like a landscape to the eye. The faculty of mind, man’s knowledge, is both these things in one, according to antiquity and the Middle Ages, simultaneously ratio and intellectus; and the process of knowing is the action of the two together.

While Pieper is not concerned with ways of viewing art per se, he is examining leisure. Art, of course, is a form of leisure, so his statements are indirectly tied to the discussion of art. One issue that Pieper addresses is the tendency in modern culture to accept ratio as the only valid form of understanding. This tendency is also present in how we view art. We are not content to simply receptively perceive art; we must always examine and question and define it instead.

It is precisely this tendency that Susan Sontag challenges in her essay Against Interpretation.

Our task is not to find the maximum amount of content in a work of art, much less to squeeze more content out of the work than is already there. Our task is to cut back content so that we can see the thing at all.

The aim of all commentary on art now should be to make works of art-and, by analogy, our own experience-more, rather than less, real to us. The function of criticism should be to show how it is what it is, even that it is what it is, rather than to show what it means.

In place of a hermeneutics we need an erotics of art.

Sontag, I think, makes a clear case for less emphasis on ratio. This, along with Pieper’s arguments in his book, seems to suggest a more balanced approach to art. Perhaps art is most fully experienced when it is appreciated as primarily an aesthetic experience.

Furthermore, Søren Kierkegaard’s argument in Either/Or for the principle of limitation as the sole saving principle of the world would seem to indicate the necessity of such an approach.

Idleness, we are accustomed to say, is the root of all evil. To prevent this evil, work is recommended…. Idleness as such is by no means a root of evil; on the contrary, it is truly a divine life, if one is not bored…. My deviation from popular opinion is adequately expressed by the phrase “rotation of crops.” The method I propose does not consist in changing the soil but, like proper crop rotation, consists in changing the method of cultivation and the kinds of crops. Here at once is the principle of limitation, the sole saving principle in the world. The more a person limits himself, the more resourceful he becomes.

What Kierkegaard is getting at is that you will only stop being bored when you stop expecting the world to solve your boredom. This is something that I wrote about even before I read Kierkegaard, and it seems to me to be true. Kierkegaard calls this “living artistically.” To live artistically is to give up hope that anything or anyone will end your boredom. This is why he says, “Not until hope has been thrown overboard does one begin to live artistically; as long as a person hopes, he cannot limit himself.” This limitation is the principle that, “seeks relief not through extensity but through intsensity.”

Therefore, it seems that the fullest experience of art is the one that seeks intensity within the limitations of the aesthetic of the work. However, it may not be clear at this point why I maintain that the sensory experience should precede the rational experience. Looking back on the previous article, my reasoning may become more clear. As shown there, art must be pursued of its own accord and not for its possible benefits. In the same way, art must be pursued as a sensory experience before the rational experience can be had.

In Sontag’s essay, she argues that contemporary viewers of art essentially view the interpretation, the rational element, as what gives art its value. That rational element is what justifies art in their minds, she seems to think. However, it is only when we stop expecting art to justify itself that we experience art fully. Thus the precedence that the rational element currently has over the sensory experience is akin to the precedence that the benefits of art currently have over art itself.

To use an example from the previous article, friends must be sought for their own sake and not for the benefits that they may bring. In friendship, the experience of friendship is sought as an end in itself before rational judgement can be made. With art, the sensory experience should be sought as an end in itself before rational judgement can be made. This is why the sensory experience must precede the rational experience, though both together, of course, lead to a full experience of art.

Having defined art, discussed methods of criticizing it, and explored ways of experiencing it, we can finally ask whether or not Andres Serrano’s Piss Christ is good art. In order to do that, it is necessary to investigate precisely what is happening in the picture. The question of whether not the work is modern or postmodern must be answered. Moreover, the piece must be examined in light of the many different criteria for artistic understanding that have been provided in the series thus far. This, then, will be the direction that our inquiry will take as the series comes to an end.

Discussion — No responses